After the collapse of the former Soviet and getting the independence, the Central Asian countries experienced huge environmental problem of global scale inherited from the former Soviet era – the Aral Sea disaster. New geopolitical and economic challenges faced by the region and their understanding served as a predetermined factor for establishing the joint cooperation in solving various water, environmental and socio-economic issues by the Central Asian states.

On 23rd of June, 1990 in Almaty the leaders of the Central Asian countries addressed to the peoples of Central Asia and issued their first Joint Statement which said:

“The ecological disaster of the Aral Sea is a critical issue for the region. In order to unite efforts aimed at restoring ecological balance in the Aral Sea basin, we have agreed to establish an inter-state commission and set the Aid Fund for the people of Aral Sea region…“.

“We appeal to the President of the USSR, the Supreme Soviet of the USSR with a request to declare the Aral Sea region as a zone of a national disaster and to make a decision on the development and implementation of the State Program for the restoration of the ecological fund, involving specialized agencies of the United Nations and other international organizations to solve the problem…”.

On the 10-12th of October, 1991 in Tashkent the Heads of water management organizations of Central Asia made a Statement on necessity to unite and jointly solve the problems of the Aral Sea.

On 18th of February, 1992 in Almaty the Heads of water management organizations signed an Agreement on cooperation in the field of joint management of the use and protection of trans- boundary water resources and established the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination.

The International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea established in 1993, played a huge role in acquiring the first experience and formation of international relations between newly emerged independent countries, and to this day it serves as a regional platform for cooperation between Central Asian countries including all stakeholders from experts to decision-makers.

Since the very beginning of IFAS operation, its President Mr. Nazarbayev N.A. paid his efforts attracting donor countries, UN structural organizations and international agencies to the Aral problem.

On 29th of June, 1993, Mr. Nazarbayev N.A., the President of the Republic of Kazakhstan, fulfilling the role of the IFAS President sent appeal to the heads of 33 foreign states, while the Prime Minister of Kazakhstan addressed to the ambassadors of 25 foreign countries, to 130 major foreign firms and companies and the world’s leading financial institutions with a request to respond on Aral issue.

Such activity successfully resulted in Donor Conference in Paris on 23rd -24th of

June, 1994 organized with the financial support of the World Bank.

Thanks to the countries’ desire for mutual cooperation IFAS successfully

implemented three programs of the Aral Sea Basin (ASBP) during the 25 years of its operation and has become a reliable partner to the United Nations in achieving sustainable development goals within 2015-2030.

Within the framework of the first and second programs of the Aral Sea Basin (ASBP-1, ASBP-2) as well as complex national programs Kazakhstan

implemented the first phase of the large scale Project “Syrdarya Control and Northern Aral Sea (SYNAS-1 )1”.

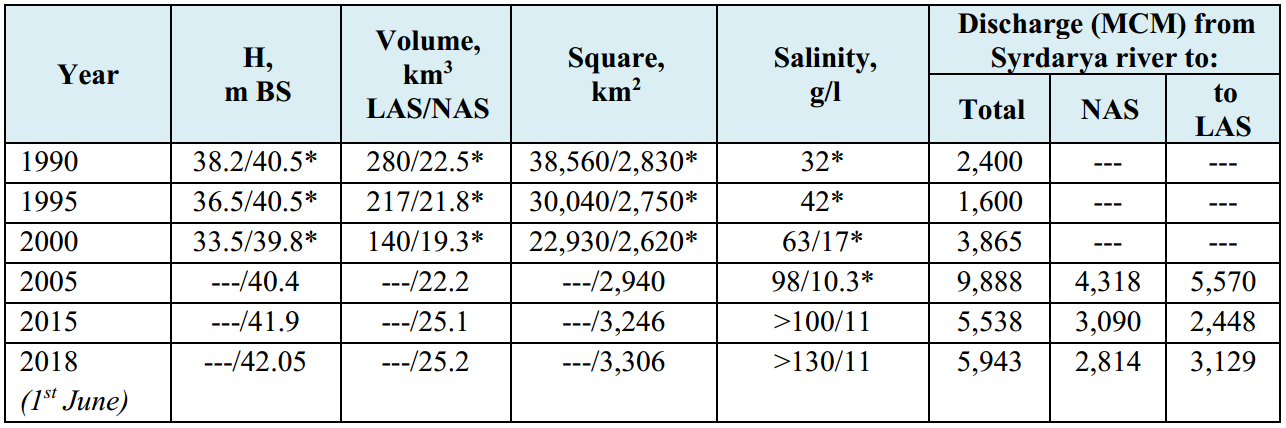

Through the implementation of the project Kazakhstan managed to preserve the northern part of the Aral Sea (Table 1), significantly improving the water management conditions in the middle and lower reaches of the Syrdarya river, toincrease the safety of hydraulic structures, reduce the number of emergencies caused by climate change and extreme hydrological runoff during the low flow period, and improving wetlands in Syrdarya downstream.

Table 1 Bathographical Data of Aral sea

Notes: BS – Baltic sea, LAS – Larger Southern Aral sea; NAS – Northern Aral sea; MCM – million cubic meter The Kokaral dam was commissioned on August 8, 2005, H – 40.24 m BS

* Data of the Institute of Oceanology, P.P. Shirshov, Russian Academy of Sciences. // The Aral Sea in the beginning of the XXI century. Physics, Biology, Chemistry. Moscow, 2011

1 The Project was adopted on 11 th of January, 1994 in Nukus while the implemented within 2002-2010

Water management improvement in Kazakhstani part of the Syrdarya river has triggered a multiplicative effect resulting in improvement of ecological and socioeconomic conditions in both Kyzylorda and Turkestan provinces (former South Kazakhstan oblast).

The below are shown direct natural indicators of the successful implementation of SYNAS-1:

• revival of the traditional fish industry and export of about 8 thousand ton

of fish to the European Union, Russia, China and other countries;

• revival of 19 lakes of which 8 are of fishery importance;

• restoration of some 50 thousand hectares of pasture lands.

Simultaneously with the implementation of the SYNAS-1 project, Kazakhstani Government launched and implemented State Sector-wised Programme “2002-2010 Drinking Water” to ensure access of the population to high-quality drinking water.

After 2010 the drinking water programme has been continued through a new “Ak Bulak” programme launched in 2011 aimed at achieving by a year 2020 the coverage by centralized water supply system of 100% and 80% of urban and rural population, respectively.

During these years more than 195 km of water supply network have been

rehabilitated and newly built only in Kazakhstani part of the Aral Sea region. Major water supply projects were implemented in Kazakhstani part of Syrdarya river basin such as construction of Aral-Sarybulak group water supply pipeline (4th phase) with laying of 22 km of cast iron pipes, Zhidelinsky, Kentau-Turkestan and other systems of group and local water supply system.

It shall be noted that water supply projects are implementing under other state programmes as well. For example under “Nurly Zhol” State Program 72 km of water supply and 4.5 km of sewer networks will be rehabilitated while by the State Program “2020 Development of Regions” 16.7 km of water supply networks will be rehabilitated in 2018 in Kyzylorda province.

In 2018 the water supple and sewerage projects have been undertaken on the new development area of Kyzylorda city – on the left bank of Syrdarya river.

However in spite of the ongoing projects there are a number of problems in the water supply and sanitation sector in Kyzylorda province. As of the first half of 2018, the share of decentralized water supply system still remains significant and reaches 33.8%, about 12% of tap water supplied to the population does not meet sanitary and chemical standards and 3.9% – microbiological standards.

Even a quarter of a century later, the problem of the Aral Sea does not disappear from the agenda. There are new works that cover various aspects of saving the “life” of the shrinking sea. The problem actively discussed in various countries has acquired a global character.

According to the data of the National Center for Occupational Health and

Occupational Diseases of the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the amount of salt from the bottom of the dried-up sea reached 114 billion tons2. And now, with strong storms, which are observed here quite often, about 150 million tons of salty and poisonous fine dust are spread each year, the particles of which are found in various parts of our planet.

The tragic drying up of the Aral Sea has aggravated the disturbance of the

ecosystem. With abrupt shallowing, the sea loses its main functions: purifying, climate-forming and thermo- regulating. The frequency of dust-salt storms has increased 10 times, forming acid rains and sharply reducing the yield of agricultural crops3.

In recent years, due to global climate change, this trend has become even stronger. So, for example, only in the current year of 2018, on May 26-29 and July 17-18, two catastrophic salt storms in the Aral Sea have already taken place, covering the territory of the Kyzylorda region (Republic of Kazakhstan), the Autonomous Republic of Karakalpakstan (Republic of Uzbekistan) and the Dashoguz velayat (Turkmenistan), causing huge damage to agriculture and public health.

In 2017 and 2018, at bilateral and multilateral meetings, the Presidents of the Central Asian countries unanimously noted the importance of developing constructive cooperation within the framework of the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea and agreed to hold the next 12th Summit of the Heads of States of the founders of the International Fund for saving the Aral sea on 24th of August, 2018 in Turkmenbashi city.

It is expected that the “Aral Summit -2018” will be focused at the issues of further regional cooperation aiming at improving of the environmental, social and economic conditions of the population in the Aral Sea basin as well as possibilities for future collaboration in the integrated use of water resources in Central Asia.

2 Sakiyev K.Z., et al. Modern Health issues of the people of Aral sea region. National Center of Occupational Health

and Occupational Diseases, Ministry of Health of RK// News Magazine of the Kazakh National Medical University,

#3(3)- 2014

3 Omarov E.O., Shek D.M., Tuleutayev K.T. Ecological and medical issues: population health of the Aral sea

region//Medical, social and ecological issues of Aral sea region. –Almaty, “Galym”, 1994.-p.57-59

In addition to the traditional questions, the Agenda shall also include the issue of capacity building and further improving the performance of the Fund in order to increase its effectiveness and deepen interaction with international and financial institutions which has been on the agenda since 2009.